Review: THE TURIN HORSE (Béla Tarr)

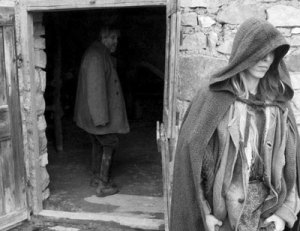

I am surely not the first to say that Béla Tarr is unrelentingly serious, and I will not be the last. Not since Alexander Sokurov’s The Second Circle have I watched a movie that felt so much more like physical endurance than an active intellectual and emotional experience. I’m sure this will lead many viewers to call it pretentious. It is certainly repetitive, quiet, minimal, long and, perhaps most crucially, very, very somber. It forces you into its rhythm sooner or later, but you never get comfortable with the tone.

The Turin Horse is a punishing film. The people in it are ugly and often cruel. Their lives are repetitive and arduous. There is little plot, little action, little change of scenery, but there are plenty of long, long takes in which no words are spoken. When a talkative neighbor drops by to borrow some liquor, his speech, rather than providing new interst, quickly becomes tedious.

The prelude tells the apochryphal story of Nietzsche throwing his arms around a brutally beaten coachman’s horse, then reminds us that we know what became of Niteszche after this episode but we don’t know whatever happened to the horse. I think this encourages some viewers to interpret what happens in the film as a punishment, but I would argue that this context is mere pretense. It is a red herring.

I hate to use the word “allegorical” because I assume people immediately start thinking of The Matrix or some such. The Turin Horse is allegorical, but it is absolutely not The Matrix. The difference between the two kinds of allegory represented by both films is that The Matrix relies on static and clunky symbols, whereas The Turin Horse is rooted in physical reality and concrete details.

Just because it is an allegory it does not necessarily follow that every image is part of code that must be cracked. So I would caution against the symbolic interpretation i.e. the potato represent this, the horse represents that. How does one make a movie about death, about the journey into death, without resorting to symbols? We are talking about representing the unrepresentable. It isn’t what the horse or the potato represents that matters so much as the texture of the horses coat or the rippling of its muscles, the photographic reality of the act of peeling and eating a single steaming potato.

A narrative needs an engine, but we must not mistake the engine for the whole machine. As Andrei Tarkovsky, no doubt one of Tarr’s great teachers, often had to explain when asked about Stalker: it is not a metaphor, it is a specific journey undertaken by specific people, and they have to confront challenges and negotiate obstacles along the way. He suggests, in short, that Stalker is not a metaphor for life; it is life. The difference isn’t an easy thing to get your head around, but if you can The Turin Horse will make more sense.

–DJ

Review: CERTIFIED COPY (Abbas Kiarostami)

It is difficult to begin writing about this film now without acknowledging the critical response to it when it was first released. At first I am baffled by the chorus of dismissal; by those who think Kiarostami is out of his element. But that is my more naïve and generous nature. If I think about for five minutes, it makes sense that reviewers and serious critics alike would trip over themselves rushing to take Kiarostami down a peg. We have no reverence for artists anymore. Even artists like Kiarostami who has proven time and time again that he is among the world’s greatest filmmakers, doesn’t get the benefit of any doubt. Apparently it’s still better to be smarter than the artist that to try to imagine that you may be missing the point of his work.

Granted, Certified Copy seems strange at first. In many ways it is a hard turn away from the Kiarostami that we know. Since when does he make films about communication breakdown between men and women in love? And what’s with the absurdist conceit of the narrative clearly stating that the two principle characters just met, but they suddenly begin playing the roles of husband and wife, and arguing as if they have known one another intimately for years?

There are familiar Kiarostami-isms of course. There’s a car ride with a shot through the windshield of the car interior and a shot of the exterior POV of the driver. There are single medium shots that remain on one character throughout an exchange of dialogue instead of the typical shot/reverse shot strategy employed in mainstream films. We are used to this from Kiarostami.

But then there are white people. In fact one of the principles is one of the most famous actresses in the world. One is tempted to say that Kiarostami’s camera treats her like the renown actor that she is, but all the close-ups and silent acting have characterized his film style, long before Kiarostami found Juliet Binoche, so it would be unfair to suggest that the filmmaker makes love to his actress the way Godard does to Anna Karina, Antoninoi to Monica Vitti, Fassbinder to Hannah Schygulla or Bergman to Thulin, Andersson or Ullman. Still, has there ever been a shot in a Kiarostami film like the one wear she dolls herself up in the washroom at the café.

To my mind this is not selling out. This is Kiarostami finding out that his style is capable of doing things beyond what he has accomplished so far. Many critics have noted that the main actor, an opera singer with no professional acting experience, is stiff and mismatched with the effusive Binoche. Well, that is precisely the point! He is a drag. He is serious, stuffy, boring, internal and inconsiderate. That they are mismatched is not a mistake, but rather it is the crux of the narrative conflict. The movie is about communication break down. It asks us to think about whether men and women can really understand one another. What is love if we cannot? How do we stay together? What do we stay together for?

All of us like to put things in categories; it is part of how we understand the world. But we should make sure that we are using the right categories. When you think of Kiarostami in terms of his subject matter and of the nationalities of the faces he usually photographs, a film about white people’s relationships may not make any sense. The onus is on the viewer to make that shift; it is not incumbent upon the artist to make a film we can fit into our predetermined categories. This is why Bresson critics don’t understand that Une Femme Douce is about love between men and women, and why Tarkovsky apostles so often fail to note the importance of the relationship between the two principles in Nostalghia. We know what their movies are about and it isn’t that. Yet, they are masterpieces. They are nuanced and sincere explorations of a subject Bresson and Tarkovsky normally merely brush against. Certified Copy now ranks alongside them, both as a masterpiece as an unexpected, misunderstood work.

–DJ

Review: ANOTHER YEAR (Mike Leigh)

The first thing I said to my friend as we walked out of Another Year was, “Can you think of another filmmaker who has gone through such a lull like that, then come back to create masterworks again?” Twelve years passed between Life Is Sweet and All or Nothing, and in that interval Mike Leigh made his weakest films including Naked, a great critical success that was basically the opposite of everything he had done up to that point, and Topsy-Turvy which seemed to caricature his own style quite like Altman’s The Company. Perhaps this context is unnecessary, but point is that I was doubly happy as I walked out of Another Year, happy to have seen such a great movie and happy that one of the greatest living filmmakers still makes masterworks.

First let us consider improvisation. I’m not talking about actors making up lines, but characters that are able to ride the flow of tones and moods, to play along with whatever that are given in human interaction. Gerri is a prototypical Mike Leigh heroine. Mary has passed out downstairs and Gerri and Tom are in bed. She confesses he concerns about Mary. There is a little back and forth before he blurts out (I am paraphrasing from memory), “You know, I never really understood history.” Gerri takes the abrupt change and runs with it. “Oh yeah?” she says, then they chat about his new topic. No more discussion of Mary, no resentment or annoyance about the change of subject. She just rolls with it. This characterizes Gerri’s entire relationship with Mary, which accounts for how Gerri is able to remain friends with Mary, despite how desperately needy she is. Leigh celebrates characters who are able adjust to the rhythms and whims of those around them.

In Another Year characters are multi-dimensional. There is no “true” or “essential,” but who they are in different situations and with different other people. There are better and worse versions of each character depending on the context, but never “the real” person. Gerri showing sympathy for Mary is as equally Gerri as the one who chides her in a later scene. She always gives Mary the benefit of the doubt, but sometimes Gerri has to put her foot down. Perhaps she considers her harmless and childlike, but there is a point where her treatment of the son’s new girlfriend gets so rude that Gerri has to put a stop to it.

When Mary shows up unannounced and desperate, Gerri is actively annoyed. She even snaps at her, another color we have not seen before, “You really should have called first, Mary.” And Gerri actually looks bad here, she looks petty and impatient when she tells Mary she was disappointed in her. Because Gerri has not seen Mary as the audience just has. She didn’t see how desperate she was when she came to the door. She didn’t see that she was able to make Ronnie smile, an amazing moment! She didn’t hear her ask Ronnie if he wanted to cuddle. Was that an inappropriate question? Was she asking for Ronnie or for herself?

This is what Leigh does and has been doing for decades. He shows that a person is not the same person from morning to night every day. People reveal different parts of themselves depending on who they interact with, even people that we think are shallow like Mary. She is not purely selfish; she wants to give. She wants to be generous. She is not annoying to everyone; some people find her charming. Likewise, Gerri is not always nurturing and forgiving. Sometimes she is petty and fed up. They are paired as opposites, Leigh indicating through his style that Gerri’s approach to life is the one he espouses, but he has great sympathy for Mary. The film does not judge Mary; it tries to understand her and so it ends up being as much about her inability to improvise, to listen to others and to think about others, as it is a celebration of Gerri’s generosity and improvisational prowess.

–DJ